When we asked Bob Olson about the culture at UVA Law in 1970, he said it was “quite collegial.” Everyone took their courses seriously, but his fellow law students were friendly. Olson knew he wanted to be a corporate lawyer, so his classes reflected that interest. His course load, combined with his duties at the Virginia Law Review, made for a rather grueling schedule. Once he had a job lined up and his tenure on the Law Review ended, he decided to take a break from his studies. He reminisced with us about riding his motorcycle, reading novels, and skipping classes, but only on occasion of course.

Barrister (Charlottesville, Va: University of Virginia, 1970). (VL 05 .B276)

Bob Olson (left), Sadler Poe ('70), and David "Dave" Lott ('70) grin on motorcycles, 1970.

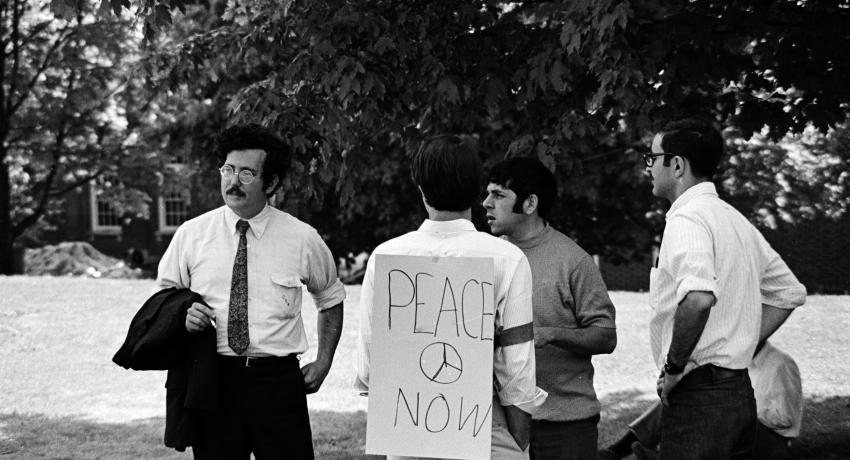

Olson felt the events of the 1960s very deeply. Like many of his peers, he was “horrified by images of police and protesters clashing outside the Democratic National Convention [in Chicago].” His disgust with police violence morphed into a piece for the Law Review in 1969 entitled, “Grievance Response Mechanisms for Police Misconduct.” Thanks to law school professor Charlie Whitebread, the final section of Olson’s note found its way into a report Dean Monrad Paulsen sent to the National Violence Commission.

Charles Whitebread (left) with law students, May 1970.

Olson does not remember exactly where or how he heard about Kent State, but he suspects that, like most people, he heard the news from Walter Cronkite. Shortly thereafter, hundreds if not thousands of students held a vigil on the lawn at UVA. The exact details of how the marshals came together after that are blurry to Olson. He remembers attending rallies and wearing his armband but does not recall who organized them and what duties they were given.

His recollections of William Kunstler and Jerry Rubin’s speeches on May 6th are much more vivid. The atmosphere in University Hall where the event took place was “electric,” Olson said. Students were yelling, “Strike! Strike! Strike!” Everyone stormed out of University Hall and charged towards UVA President Edgar Shannon’s house. On May 8th, Olson had just driven by University Hall that morning where he saw an “immense sea” of Virginia state police cars surrounding the area. Another marshal—David Lott—called Olson and urged him to come to the scene where state police had just invoked the Riot Act. Police were arresting anyone and everyone in sight. Soon, Olson found himself amongst an unlucky lot of arrestees shoved into a Mayflower moving van. Olson had approached the Lawn where police were chasing people down. When he turned, an officer stood before him and declared that he too was under arrest.

Bob Olson describes the sequence of events leading to his arrest on May 9th.

Once in the van, Olson and his “fellow Mayflower prisoners” exchanged stories. It had all started with the “Honk-for-Peace” rally earlier in the evening. Police ordered everyone to disperse and then made mass arrests of students, passersby, fraternity members, and of course the Shakey’s Pizza delivery man. Olson described the scene in the van as “lively.” When they arrived at the police station, everyone was processed individually. Some were released on bail. Others, Olson included, spent the night in a cell. He was let go early the next day, likely due to the efforts of Law faculty like Charlie Whitebread.

The “Days of May” had finally come to a close, but the charges brought against Olson followed him. In an effort to avoid the draft, Olson had applied to join the New Jersey National Guard. When he graduated, he received word his application had been accepted. Olson passed his written exams, signed his contract, and took the oath, but when the captain learned that he had been arrested and criminal charges were pending, he was told to come back when the matter was cleared up. A couple of weeks later, President Richard Nixon announced the end of the draft. Olson called up the captain and said he did not want to join the National Guard after all. His charges were dropped later in the year.

Reflecting on May Days, Olson feels marshal and student efforts were worthwhile. The protests created a common bond as well as a feeling of empowerment they could carry with them.