Lane Kneedler originally wanted to be a chemist. After completing his undergraduate degree at Gettysburg College, he went on to pursue a PhD in Chemistry at Princeton University. When he left Princeton, he had to fulfill a two-year obligation to the Army ROTC. Kneedler was assigned to the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps where he learned to conduct investigative interviews. Kneedler visited the University of Virginia and has been here since.

Kneedler enrolled at UVA Law in 1966. Back then, the culture was “really very interesting.” He recalls that men wore suits and ties. Even a sport coat was considered informal. During the early days of the anti-war movement, this "uniform" carried over into student demonstrations.

UVA students call for a more diverse Board of Visitors in February, 1969, during the "Coat and Tie Rebellion."

Kneedler developed a particularly close connection with Professor Peter Low. Kneedler speculates that it was this connection that eventually led to him being hired as Assistant Dean right after he graduated. In the spring of 1969, Kneedler had already accepted a job with a New York law firm when Dean Monrad Paulsen called Kneedler into his office and convinced him to join the faculty. As an assistant professor and Assistant Dean, Kneedler was responsible for teaching one class and for running all administrative functions of the law school, including maintaining the budget and salaries.

Despite growing tensions at the University related to the escalating war in Vietnam, Kneedler recalls that from his perspective as a faculty member, it was “business as usual.” In a matter of days, Nixon expanded the war into Cambodia and National Guardsmen fired at protestors at Kent State which left him “appalled.” As student leaders established the Law School Boycott for Peace Committee, Kneedler maintained his schedule of teaching on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays despite growing unrest.

Wednesday, May 6th was “Freedom Day,” and Kneedler remembers attending the William Kunstler and Jerry Rubin speeches at University Hall. As a faculty member, he said he was nervous because it was “clear that the movement to shut universities had, in fact, come to Virginia.”

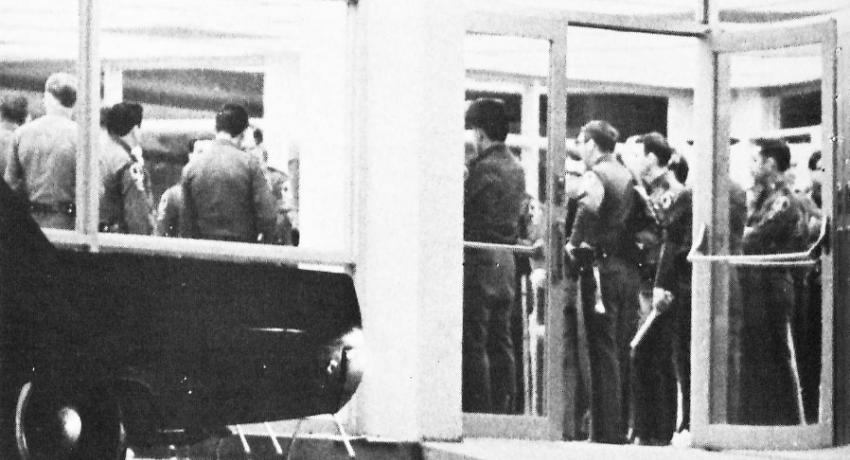

Two nights later, on Friday, May 8th, Kneedler was in his office when he learned that 68 students had been arrested and carted away to the police station in a Mayflower van. Someone told Kneedler that they were looking for lawyers, including Law faculty, to represent the arrestees and try to get them released, so he went down there.

Police officers, arrestees, and legal officials gather inside the Charlottesville City Police Station during the early hours of May 9th.

Each person was called one at a time with their representative. Kneedler recalls representing one of the lead activists. At some point, he ran into his friend, Alton Leake, who was a groundskeeper that lived in a cottage behind Carr’s Hill. Leake was one of the arrestees.

Back on Grounds, Kneedler feared that unrest would shutter the university. Then came President Edgar Shannon’s speech on Sunday, May 10th. The Lawn was packed, and the tension in the air was palpable. When Shannon announced that he disapproved of Nixon’s actions in expanding the war in Vietnam, “it was like puncturing a balloon.” The students and faculty were relieved.

As the end of the semester quickly approached, a new question arose: What to do about final exams? Many students had already left Grounds or simply were not coming to class. Law faculty debated whether to cancel finals completely, or to punish those that did not take their exams in person at the law school. Both options seemed impossible and unfair. In the end, Kneedler spearheaded what became the flex exam system: students could either take their exams in person like normal or take them remotely with an exam proctor who had also graduated from the university. Kneedler muses that “that was putting a heavy burden on the honor system” but, in the end, if there were any violations, he never heard of any.

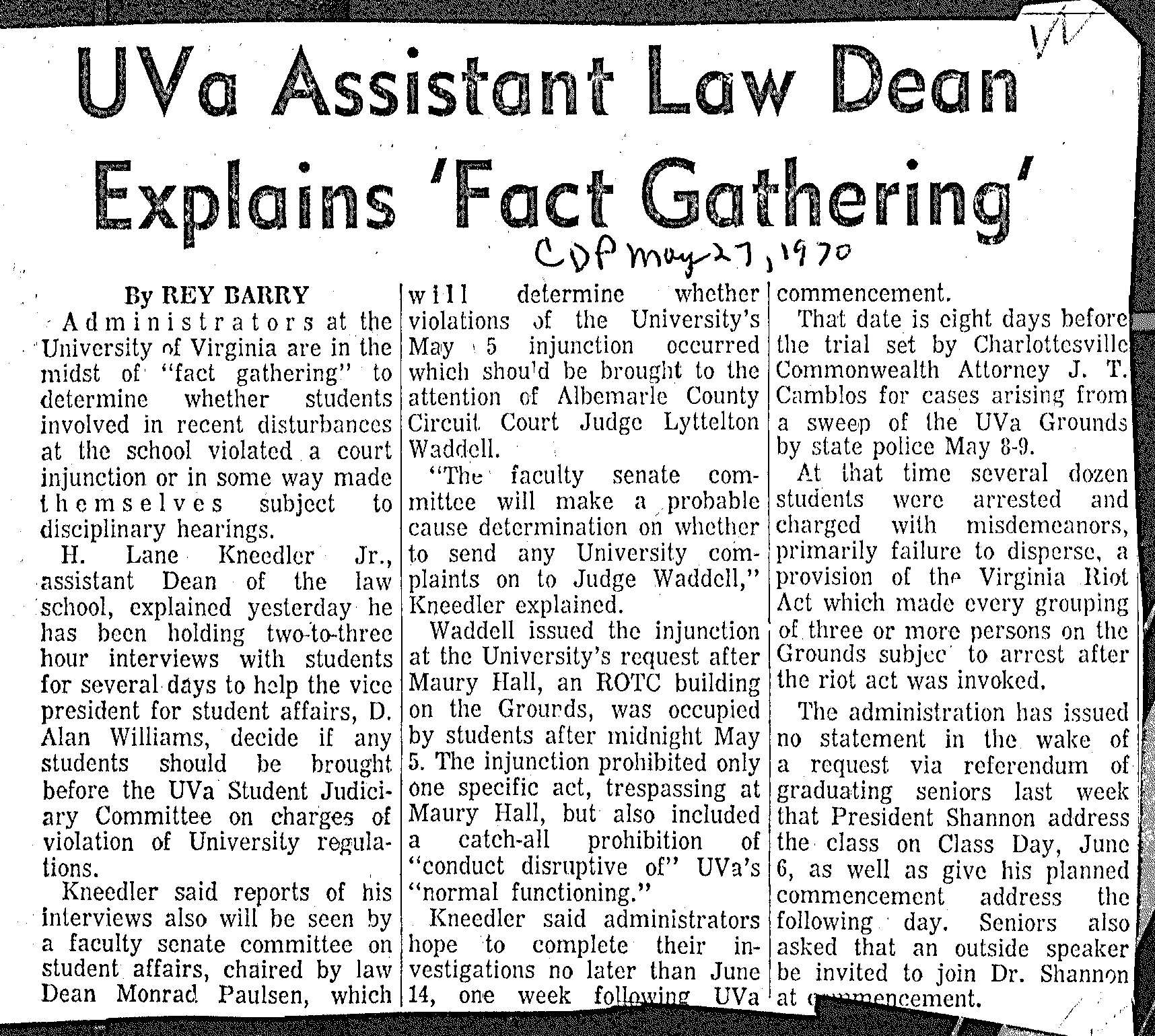

The final episode in Kneedler’s May Days experience is his investigation of the sequence of events, which he conducted over the course of that summer. President Edgar Shannon initially asked Dean Monrad Paulsen to conduct the investigation and produce the report, but Paulsen tasked Kneedler with the effort based on his investigative background from his time in the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps. Through telephone and in-person interviews, Kneedler compiled hundreds of pages of notes, broadsides, and legal precedent. As he neared the end of his research, Paulsen told Kneedler that the administration had decided to drop the investigation and ordered him not to move forward with the report.

Charlottesville Daily Progress, May 27, 1970. CCBY Image courtesy of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia

Newspaper clipping from the Charlottesville Daily Progress, May 27, 1970.

When we asked Kneedler what his perspective is on May Days fifty years later, he applauds President Shannon for denouncing the war. Although the student strike movement never turned violent like it did at other universities across the nation, Kneedler believes the student strike movement contributed to the overall end of the Vietnam War.